When an inconsequential fishing boat, the St Anthony left southern India to fish for tuna on February 2012, its crew of 11 had no idea they would soon be at the centre of a major international incident.

While anchored at sea, approximately 20 nautical miles out from India, the ship was fired upon by an Italian naval vessel, the Enrica Lexie, having allegedly mistaken the ship for a pirate vessel. Indian police arrested two Italian marines for the incident, remanding them to custody and charging them for the deaths of two sailors who were killed in the attack.

The Italian government disputed the arrest, arguing the incident occurred in international waters, meaning India had no jurisdiction over the marines. By the Indian government’s judgement, the incident took place in Indian waters, ruled as within 24 nautical miles of the coast under international law. While the government eventually downgraded its charges against the marines from murder to violence (meaning the marines would not get the death penalty if convicted), the Enrica Lexie case created a permanent rift between India and Italy.

Fast forward to January 2015 with the two countries still at loggerheads, the European Parliament attempted to intervene. They called for India to repatriate the marines to face trial under Italian jurisdiction, as their detention in India was seen as a breach of human rights. It goes without saying the Indian government were not happy with the EU taking this stance, and the intervention has threatened to obstruct the slow build-up of India/EU relations.

While the argument with Italy may have hindered relations with India, it is not the first EU state to have quarrelled over matters of jurisdiction. Look no further than the Purulia Arms Drop case incident in 1995, where Danish citizen Kim Davy (real name Niels Holck) was accused of supplying weapons to the right wing religious organisation Ananda Marga in West Bengal. Similar to the Enrica case, the incident sparked a diplomatic riff between Denmark and India over matters of extradition and the committing of war crimes on foreign soil.

However, there is one member state with which India still has a close-standing relationship: the United Kingdom. Despite being steeped in colonialist history, the close relationship between the two nations still holds strong today. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi seems to think so, calling Britain “an entry point for us to the European Union”, on his visit to the country in November 2015.

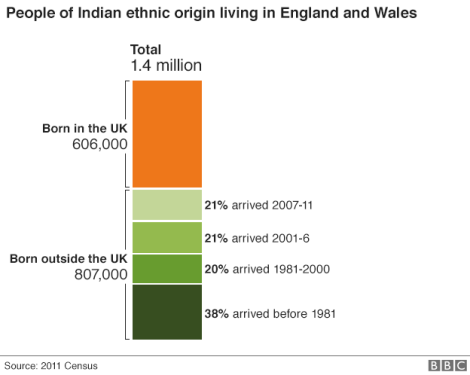

The UK has strong cultural ties to India. Boasting a higher Indian population than anywhere else in the EU (roughly 1.4 million according to a 2011 census), and a fairly open cultural cross-over as evidenced by the popularity of Indian cuisine in the United Kingdom and the success of UK media centred around Indian culture such as Bend It Like Beckham and Slumdog Millionaire.

The problem with relying on the UK for entry to the European Union is that the UK itself has never been particularly close with the EU. It has a reputation among other member states for playing loose with EU principles, and the ongoing Brexit debate threatens to sever ties with the Union completely. Even in the event of a “no” vote, the sheer prominence and weight behind the campaign could potentially hurt the UKs reliability and standing within the EU for a number of years. Whether it stays or not, the UK has cemented its opposition to the principles of a European superstate; David Cameron made that clear in his campaign for a “no” vote. The question then becomes whether or not India can afford to rely on them as a potential ally.

Since Prime Minister Modi took over as Indian prime minister in May 2014, he has attempted to boost India’s economy through foreign trade in order to compete with China. As the largest single economic power in the world, and China’s second largest trading partner, the EU is a natural fit with his goals.

The EU and India have more in common than most think; they are both comprised of a similar number of states (28 and 29 respectively) largely pulled together in the chaotic post-war reconstruction of the 1950s. Deepening relations with India would grant the EU influence in one of Asia’s fastest growing economies. It’s a partnership that stands to benefit both sides, but the constant disputes with individual member states, as well as disagreements with the broader EU at the trade level have interfered with any meaningful developments.

The EU and India have been attempting to negotiate a Bilateral Trade & Investment Agreement since 2007. The agreement, if signed, would link the two economies together by liberalising trade and removing tariffs. But instead negotiations have been constantly stalled while the EU and India battle over a number of small trade disputes.

A recent example of this was the Netherlands’ seizure of Indian-produced pharmaceuticals on patent infringement grounds in 2010, many of which were in transit to third party countries such as Brazil. That dispute, which led to India cancelling a round of FTA negotiations that year, was resolved by mutual agreement in 2011. Other issues are still being debated, such as the EU imposing anti-dumping measures on exports in India.

It is likely due to these negotiation difficulties that Modi wants to use the UK as a gateway into Europe. The UK is the third largest source of foreign direct investment in India and the value of UK imports from India currently sits at £4 billion. Despite this, as India continues to grow, the UK has fallen behind countries such as the US, Singapore and China in terms of what it can offer economically. Its real power lies in its cultural ties to India and its potential to act as a moderator between India and the rest if the EU, which threatens to be diminished by the Brexit debate.

The UK is still held in high regard in India, and may continue to do so for the foreseeable future. According to a survey India Matters, published by the British Council, the UK was rated the second most attractive country behind the US by young Indians in terms of education, culture and infrastructure. 75% of Indians surveyed were shown to have a positive attitude towards the UK. So even if a “yes” vote in Brexit comes to pass, India and the UK are unlikely to lose favour with one another.

The European Union and India have much in common with regards to their global standing and goals. Both seek to establish themselves as an economic power, both rose to unification in the aftermath of the Second World War, and both have found themselves needing to counterbalance China’s growing might in Asia. But incidents such as the Enrica Lexie case, and the argument-laden nature of trade negotiations are preventing either of them from achieving a stable, positive and long-term economic relationship. Now India’s best European ally is looking to leave. If that were to come to pass, Prime Minister Modi would have to look for another avenue to smooth over tensions with EU member states.